The Philadelphia Department of Health decided to cease distribution of COVID-19 vaccines to Philly Fighting COVID, the biggest clinic the city had at the time, due to privacy policy changes. These changes allowed medical information to be sold after the organization became a for-profit Jan. 25.

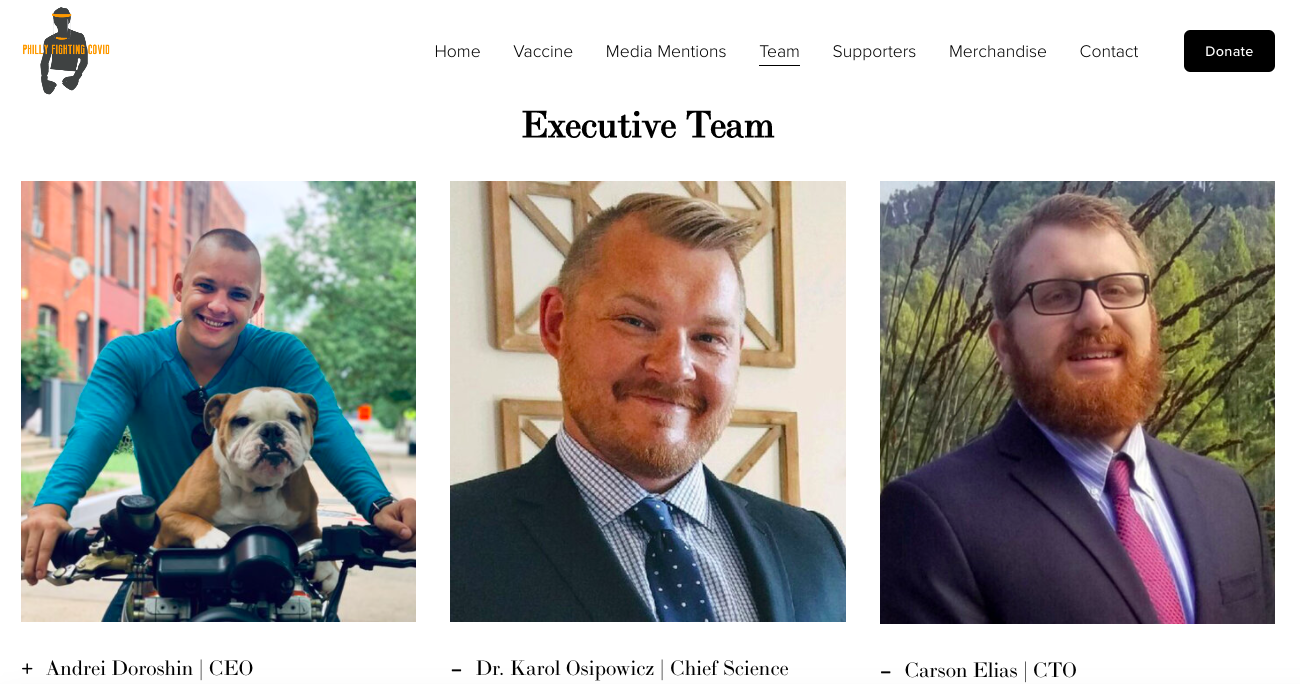

Although Philly Fighting COVID, run by 22-year-old Drexel student Andrei Doroshin, has no direct ties with Drexel as an institution, many board members, staffers and volunteers were part of the Drexel community. Besides the CEO being a student, its chief science officer was Karol Osipowicz, an assistant teaching professor in the Department of Psychology — and Doroshin’s academic advisor — and its head of systems was Johnathan Lawless, a Drexel alum (Class of 2019) whose main experience was his co-op experience with Johnson & Johnson.

Philly Fighting COVID began as a PPE nonprofit which made face shields for health care professionals using a 3D printer. Then, they began offering free COVID-19 testing opportunities to Philadelphians, including a testing center at the Fillmore (currently closed due to the pandemic) in Fishtown. However, the organization shifted its focus at the beginning of 2021 to COVID-19 vaccines, hosting the biggest vaccination center in the city at the Pennsylvania Convention Center.

Philadelphia Health Commissioner Thomas Farley said in a virtual press conference Jan. 26 that the Department of Health decided to suspend their vaccine distribution because Philly Fighting COVID’s new privacy clause was inappropriate. The Department of Health did not feel at that point that Philly Fighting COVID was a trustworthy organization.

Farley confirmed that PFC said they had not sold any information yet and that the City’s law department will make sure that does not happen.

“Up until that time they had vaccinated a lot of people, and so there was a lot of good that came out of that, but we found […] that having a trustworthy organization was very important and so that’s when we stopped,” Farley said. “At that point, as far as [private patient data], now the organization is saying that they have no intention of selling that information and haven’t done that yet.”

Farley also clarified that they were made aware of PFC’s shift to for-profit after it had occured, but he also said that this change was not the reason for the halt in COVID-19 vaccine distribution. The Department of Health distributes the vaccine to other organizations, like the Rite Aid pharmacies, who are for-profit. The action that made PFC a non-trustable organization was the change of language in the privacy policy, Farley explained.

In response, PFC put a statement on their website addressing the stop of vaccine distribution from the City and the change in policy.

“There was a language in our privacy policy that was problematic and as soon as we became aware of it, we removed it. I apologize, for the mistake in our privacy policy,” wrote Andrei Doroshin, CEO of PFC and BS/MS Psychology student at Drexel’s College of Arts and Sciences, in a statement that also later shared on their Instagram. “We never have and never would sell, share or disseminate any data we collected as it would be in violation of HIPAA rules.”

However, there were other warning signs about Philly Fighting COVID. When the city announced its own vaccine-interest website, the health department revealed that they did not have access to the data that PFC had accumulated in their own registration website, WHYY reported. The organization also lost key demographic data after its first days of vaccinating, due to an Amazon cloud glitch.Additionally, when PFC began its vaccination operations, they unexpectedly ceased their testing operations, abandoning community groups who relied on them for free tests. According to WHYY, PFC said they stopped testing because of low demand.

Doroshin was later accused by an on-site nuse of taking vaccines outsides the clinic in another WHYY article published Jan. 26. That same day, the organization had already rejected a number of people over the age of 75 because the clinic was overbooked, the article reported. Additionally, WHYY had numerous sources saying they had seen images of Doroshin wearing a suit and holding a syringe before a seated person in what appears to be someone’s private residence. Philadelphia Magazine then reached out via text message to Doroshin regarding the allegations, to which he answered: “This is baseless, I have no idea why they are saying this.”

The same day the article went live, Health Commissioner Farley said that any leftover vaccines from clinics any day had to be returned to the Health Department.

However, on Jan. 28, Doroshin admitted in an interview with NBC’s “Today” that he took doses home, saying four were left over after the mass vaccination clinic. He said he and his team called everybody they knew and he had to take them because they were about to expire.

Doroshin admitted that he is not a nurse and is not qualified to give the vaccine, but stated that he had undergone their internal certifications.

“I stand by that decision. I understand I made a mistake [and] that is my mistake to carry for the rest of my life, but it is not the mistake of the organization,” Doroshin said in the Today interview.

Additionally, in a press conference organized by Doroshin Jan. 28, he said that 100 vaccines were leftover and would expire by the end of that day. Doroshin said the entire PFC staff was calling everyone they knew, including people who had missed appointments earlier that day or during other days, and they were able to vaccinate 96 people. In the end, he decided to give the four vaccines left to other people he knew who were not eligible in the current vaccine phase. Doroshin said he thought it was ethical to put the vaccines to use instead of letting them go to waste.

“We’ve done more vaccinations than anybody in the city on a community level and this is what we get,” Doroshin said in his press conference. “The political reasons [that stopped distribution] are that there were some groups that were not happy that we got the vaccine first. They told Dr. Farley and he pulled the plug; nobody at the health department was happy about this. We had a good model, we were doing the job, we had quality.” Doroshin admitted there were some issues but “not ones to kick us out of the city and throw us out of the bus for.”

The Philadelphia Health Commissioner said he wishes the City had not worked with Philly Fighting COVID, but that PFC seemed like the best solution at the time.

Drexel President John Fry sent an email to the university community on Jan. 28 clarifying that this organization is unaffiliated with the University. The email assured that Drexel Universty had no involvement with the formation or management of PFC. He added that members of the City Council have called for an investigation into Philly Fighting COVID’s contract with the city, but Drexel is not a part of those investigations.

“Drexel’s College of Nursing and Health Professions had made arrangements with Philly Fighting COVID earlier this month for Drexel nursing students to use their vaccination site for clinical rotations, but that never transpired,” Fry added in his email.

Similarly, the Dean of the College of Arts and Sciences sent an email statement on Jan. 29 clarifying the separation of Drexel from PFC.

On Feb. 3, Fry sent a more detailed email showing sentiment and solidarity towards how the situation impacted the community.

“All of us are deeply disappointed by the news about Philly Fighting COVID, founded and led by a Drexel graduate student, and its controversial collapse. We are very concerned about the potential for harm to the Philadelphia community by the abrupt withdrawal of badly needed coronavirus testing,” Fry wrote. “We are frustrated, as well, by the setback to the essential work of building trust in the COVID-19 vaccine — particularly for the Black and brown communities long wary of the medical establishment.”

Fry also expressed that, despite the mistakes of PFC, he believes that the majority of student enterprises from Drexel are responsible and characterized by generosity, creativity and respectful collaboration.

“The many faculty and students who volunteered for the city’s testing and vaccination efforts were selflessly giving of their time, with the understanding that they were working with this organization and the city to address a national and local crisis,” Fry added. “At the same time, we do need to look for ways to learn from the concerns raised by the Philly Fighting COVID experience, to continue to support and engage with our neighbors, and to rebuild any erosion of trust.”

Fry’s email reminded the community that there should be no room in Drexel’s campus culture for risk-taking that endangers ethical standards or causes harm to communities. He also noted that the Drexel community should insist on anti-racist approaches in all enterprises, especially ones with a healthcare focus.

After the City broke off its partnership with Philly Fighting COVID, PFC deleted its list of staff from its website because staffers were being harassed, Doroshin said. However, some media outlets noted that the biographies of some staffers were used to bolster images, including Doroshin’s himself.

“The 22-year-old’s resume boasts of his C-suite endeavors: CEO of a real estate firm; CBO of a biomedical tech organization; a filmmaker. In high school, he says, he attempted to change Southern California air-quality legislation through a nonprofit called ‘Invisible Sea.’ Invisible Sea, however, raised only $684 of its $50,000 goal,” the Philadelphia Inquirer wrote.

When the Inquirer questioned Doroshin about his achievements, he responded, “I’m from Drexel, we all do that. Who didn’t when they were 22 to pump their resume up?”

The Health Department had originally decided to work with Philly Fighting COVID, despite PFC not being run by medical professionals. When questioned about the decision, Health Commissioner Farley said that the Department of Health had established a history with PFC after they provided testing services for the city for several months.

“In the beginning, we got a lot of doses at once to vaccinate healthcare workers, but we had to get a lot of home health aids, low-income workers who are unaffiliated with hospitals vaccinated quickly. So, we had that history with them for the testing services they had what looked like a good plan, and we had staff there at the initial site and the vaccination worked well,” Farley said. “We got 2,500 people vaccinated in two days and so, it looked at that time, like this was a success. This other information came subsequently.”

Farley also said that the city’s major medical institutions would be too busy vaccinating their own staff and handling surging COVID patients to be able to help on the community level. However, when pressed by WHYY reporters in a press conference, Farley admitted that he never actually asked for the hospitals’ help.

“The Health Department later clarified that, on a routine Dec. 22 call with the hospitals’ chief medical officers, emergency preparedness, and on-site vaccine management staff, a Health Department staff member asked if hospitals would be willing to vaccinate populations beyond their own staffs. Many health systems expressed openness to supporting vaccinations of other populations after their workforce had also been vaccinated. Farley was not on that call,” WHYY wrote.

Additionally, another nonprofit organization was offering testing services and was still waiting to begin vaccinations: the Black Doctors COVID-19 Consortium. This organization is composed of medical professionals and has been offering these services for the Black community for months. However, they just began vaccinations through a drive-thru service some days before PFC stopped working.

PFC’s unexpected collapse affected a lot of Drexel nursing, pre-med and medical students. Many of these students volunteered and saw this as a great opportunity to get invaluable experience in the testing and vaccination sectors during a worldwide pandemic. Now, they may be unable to use the experience in any job or school application materials due to the controversy.

“A lot of us just took it as a great opportunity for pre-med students and for nursing students. Honestly, at the time, it seemed really great,” said a Drexel student, who was able to volunteer at Philly Fighting COVID but decided to remain anonymous for this interview. “We got to help with registration, directing patients to where they were supposed to be, serving patients during their 15-minute intervals when they were being watched [after having the vaccine]. We also got to fill syringes under the supervision of an RN and the supervision of nursing professors at Drexel.”

This week, while investigations on PFC are underway, City Councilmember Cindy Bass took the unusual step of asking Mayor Jim Kenney himself to testify about the administration’s now-severed partnership with the group. However, Kenney denied, writing in a letter to Bass that he has “no unique knowledge that could assist City Council in its investigation.”

“I cannot recall a time that a sitting mayor has been subjected to questioning by a City Council committee investigating an issue,” Kenney wrote. “I share your frustration and disappointment regarding Philly Fighting Covid, and like you want to ensure all questions are answered in an expeditious manner. Philadelphians’ lives are at stake and we need to rebuild that trust immediately,’” the Inquirer reported.

Bass was among other Council members who participated in previous PFC events, like their grand opening at the Convention center.

Now, the Health Department is managing all patients who had vaccine appointments with PFC and were expecting their second shots. This week, they reopened the Convention Center for vaccine distribution.

Andrei Doroshin and Karol Osipowicz did not reply to The Triangle’s request for comment.