Stranger and stranger. The 2020 political season has already been bizarre, and the surprises keep coming. At the same time, some things have been as predictable as the sun rising.

It was no surprise that Donald Trump would finger Joe Biden for his likeliest Democrat opponent for president and work to smear his name as vigorously as possible. It was a surprise that he would do so by putting pressure on a foreign leader to get dirt on him over the telephonic equivalent of an open mic, forcing Nancy Pelosi to do the last thing she wanted and institute impeachment proceedings against him. That ate up most of the political oxygen for several months before coming to its inevitable end with Trump’s acquittal in the Senate on a party-line vote. And Pelosi hates to lose on anything.

Mind you, I thought the impeachment was essential. Trump’s entire presidency has been a walking advertisement for impeachment. Crimes in plain sight need to be prosecuted, and a presidency that has been one long crime demanded it. Still, it was a lose-lose proposition under the circumstances. Not to impeach would have meant that the constitution would be a dead letter in the face of a despot. Not to convict would have meant that the political system was unable to make it work, the good guys notwithstanding. Choose your poison, but drink you must.

Bernie Sanders running for president again was also a foregone conclusion. Sanders was reportedly willing to defer to a run by Elizabeth Warren against Hillary Clinton in 2016. However, having won twenty-two primary contests and shaped the first reform movement in American politics in thirty years, he was going to go for broke this time around. Sanders built a formidable political organization in the interim and raised far more money from small donors than his rivals did from the billionaire class.

Then came his heart attack in November. Many, myself included, thought this would be a fatal blow for a 78-year-old candidate who looked every one of his years. But Sanders had the bit between his teeth and was not about to let go. Remarkably, he came back. He won the popular vote in the first three primary contests and buried Joe Biden with fourth- and fifth-place finishes in Iowa and New Hampshire, with a distant second in Nevada. Suddenly, he was not only a frontrunner but also an odds-on favorite. There were still other candidates in the race, including Warren, but Bernie’s army seemed an unstoppable juggernaut.

Then came South Carolina.

South Carolina was, as Joe Biden said, his “firewall”: a rural conservative state in the Deep South with a black population that wouldn’t hold it against him that he called the segregationist Senator James Eastland a political mentor and happily rubbed elbows with Strom Thurmond, an avowed racist. He’d been Barack Obama’s vice president, and that (along with a timely endorsement by the state’s most important political figure, Congressman James Clyburn) was all he needed. Sanders had been close to him in the state polls, but Clyburn made the difference. To be black in the South, the descendent of slaves and Jim Crow-era tenant farmers, meant not to expect much out of the American Dream. Sanders might promise you free college tuition and college debt forgiveness, but you hadn’t gone to college and your kids weren’t going there either. Biden had been with Barack. He might not help you much — Obama hadn’t done that either — but he wouldn’t hurt you more either. You got the high sign from the one black politician in the South with national clout, and you were in.

Biden pulled away and won South Carolina. He didn’t win by a bigger margin than Sanders had in Nevada with Latino votes, but it was enough to galvanize the national Democratic establishment behind him. The overwhelming objective was to stop Sanders. There were no illusions about Biden. He had been the presumed frontrunner the previous summer and tanked badly. Despite his decades of devoted fealty to Wall Street interests, his fundraising lagged badly behind his competitors. His ground organization was so inept that even Clyburn, in endorsing him, chided him on it, as did Terry McAuliffe of Virginia in throwing in his own endorsement. Here was a guy who’d been in politics for nearly 50 years, being told how to play the game like a rookie.

Biden had actually done no better at winning the black vote in South Carolina than Sanders had in winning the Latino one in Nevada, and Latinos are a larger portion of the Democrats’ national base, especially in electorally competitive states. But the establishment message was that the black vote was more critical, and it sold. The Super Tuesday primaries that went a few days later gave Biden an overall delegate edge, albeit a small one. Then the second chain was yanked. Two other presidential contenders, Pete Buttigieg and Amy Klobuchar, dropped out of the race after South Carolina, endorsing Biden as their campaigns ended. Mike Bloomberg followed suit the day after Super Tuesday, also endorsing Biden and promising him his big checkbook. Warren quit her race just after that. And Kamala Harris, who’d dropped out of the race months previously, put her dime on Joe, too.

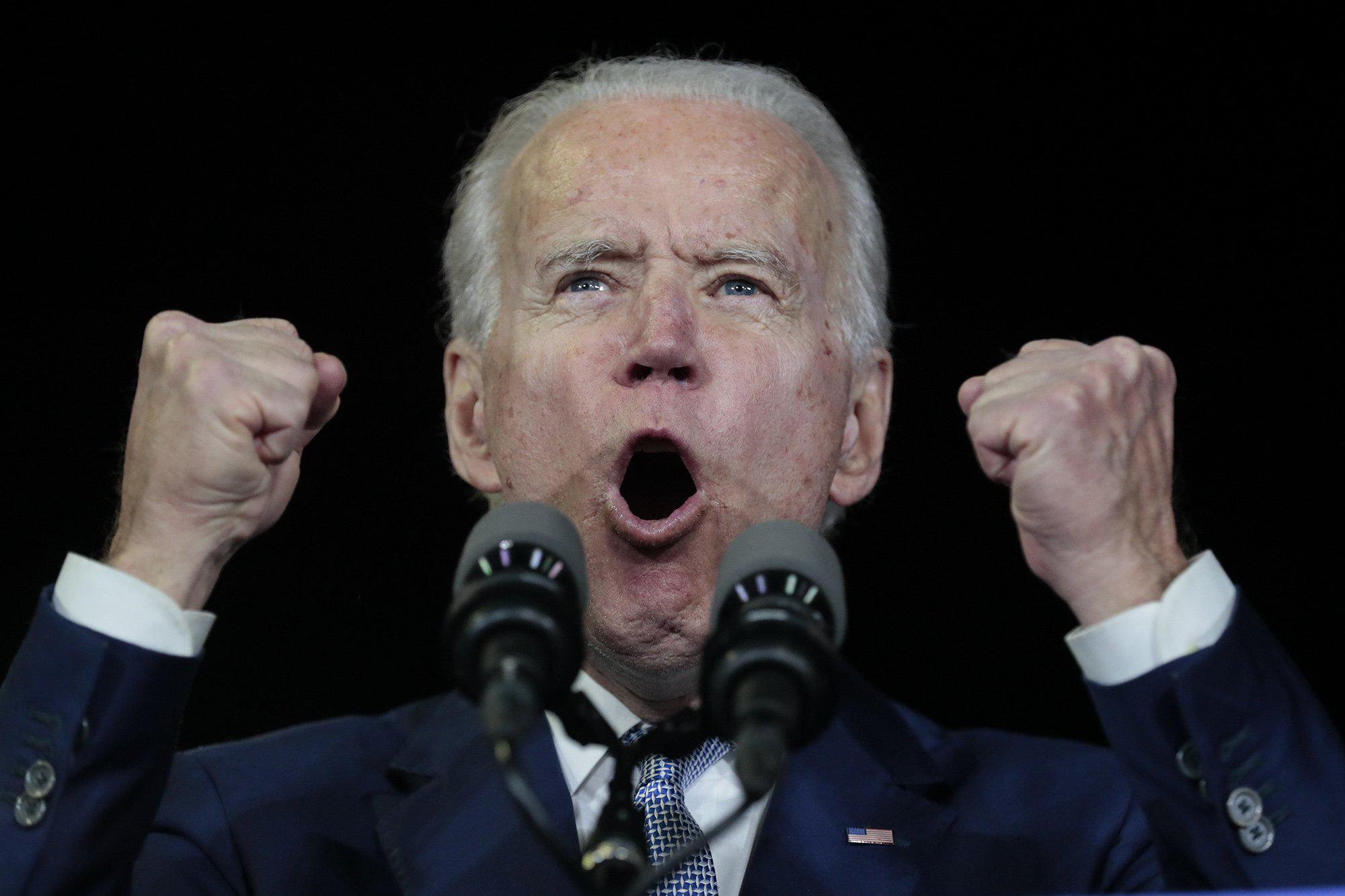

Biden appeared on his victory stage with the look of Lazarus, the only man previously raised from the dead. Biden was so dazed that he momentarily confused his wife and sister, who stood to either side of him.

All of this seemed all of a sudden, yet how could it have been otherwise? No other so-called centrist candidate had emerged with enough consistent support to clear the field. Warren, left of center, had scuttled herself over health care taxes. Biden was the familiar brand. Sanders was the firebrand, to be stopped at all costs. All Joe needed — or all the party elders needed to throw him the rope — was a win somewhere, somehow. The place where the confederacy was born gave him, after three presidential runs dating back to 1988, the first primary win of his career.

No one should place bets on how all this will turn out, but the center seems to be holding for the Democrats. Sanders has been running, a second time, for the presidential nomination of a party he refuses to join as a member. That makes him, for all the pleasantries he exchanges on the debate stage or in Democratic caucuses, not only an outsider but also a subversive. He wants to remake the Democratic Party as a genuinely progressive one, unbeholden to corporate interests and ready to seriously address climate change and economic inequality. Although he has nudged his rivals to the left, his programs are genuinely transformative and entail a fundamental reshaping of American politics. That’s why he calls his campaign a movement and his movement revolutionary. It is. And Democratic Party bosses want none of it, because it would mean the end of their reign.

That’s why Joe Biden is back.