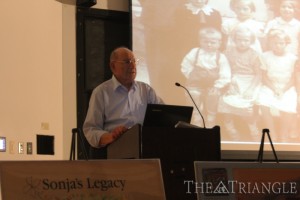

Jewish and non-Jewish students alike gathered in Mitchell Auditorium April 9 to recognize Social Justice Week and hear the story of Robert Fischl, Holocaust survivor and professor of electrical and computer engineering at Drexel.

Attendees listened intently as Fischl addressed Drexel for the first time about his memories of the Holocaust and the story of his cousin, Sonja Fischerova, who was murdered in Auschwitz. Fischl particularly emphasized artwork done by his cousin while in Terezin concentration camp.

Born only two months apart in then-Czechoslovakia, Fischl and Fischerova were cousins and inseparable friends. Fischl began his talk by sharing photos of family and friends from before the war. When unable to identify some subjects in photos, Fischl said, “One of the things of the Holocaust was we were all uprooted and all of these friends are gone. We don’t know who they are, their names, what happened to them — nothing. We don’t know anything.”

Fischl continued with photos of his home village of Kilcany, pointing out his home and even his bedroom. He explained that his family was not particularly religious; their village consisted of only 15 families, and only two, including his, were Jewish. They didn’t even have a synagogue. Even so, as Fischl was explaining the one-room schoolhouse his grandfather had built, he said, “I got to the third row, and then the world changed. I never finished the third row.”

When the Nazis occupied Czechoslovakia, the Gestapo displaced Fischl’s family, forcing them to move to Prague, where they lived with his grandparents. Only 7 years old at the time, Fischl said, “As far as I was concerned, I didn’t have to go to school. My grandmother spoiled me, and I could play with Sonja all of the time.”

Immediately upon moving to Prague, however, Fischl said his father began searching for a way out. Fischl’s family eventually obtained certificates, tickets and visas to go to Palestine, and he recalled saying goodbye to the rest of his family for the last time in January 1940. He described Fischerova and her family as some of the “unlucky ones.”

Fischerova, along with her mother, sister Renee and grandmother Anna, were deported in 1942 to Terezin (or Theresienstadt) concentration camp in Czechoslovakia when Fischerova and Fischl were both 11 years old. Each person was allowed one suitcase to store belongings. One woman, Friedel Dickers Brandeis, filled her suitcase with as many art supplies as possible instead of personal belongings.

Brandeis began what Fischl describes as an art therapy class for children, as they were too young to work in the concentration camp. With Brandeis’ help, 4,500 drawings were made, and she made sure each one was signed by the artist. She also graded each piece based on strength, intensity, dimensions, forms, character, composition and color.

Terezin began “beautification” in 1944 to prepare for an inspection by the International Red Cross. The buildings were painted, coffee shops were built and a soccer game was even organized to show the Red Cross that Jews were being treated with dignity. A propaganda film was even created to show the rest of the world “what it was like” in Terezin.

However, as Fischl explained, in order for Terezin to seem beautiful and not overcrowded, 7,500 Jews boarded a train in May 1944 for the 270-mile ride to Auschwitz. Fischerova, her sister and her mother were among those sent to the gas chamber upon arrival. Brandeis’ husband was also deported, but because of his carpentry skills, he wasn’t immediately killed.

Without her husband at Terezin, Brandeis had little desire to carry on, according to Fischl. In August 1944, she volunteered herself to go to Auschwitz to be with her husband. When she got there, she was also sent to the gas chamber.

Before leaving, Brandeis stored all artwork done by the children in a trunk hidden in the attic of the engineers’ barracks in Terezin. She told other members of the camp about the artwork, and after the war they were recovered. The children’s art has since been displayed in a synagogue.

Fischl stumbled upon Sonja’s art by chance during what he calls his family’s “roots trip.” Looking at all the artwork in the synagogue, his daughter pointed out a piece by Fischerova titled “Cleaning the Dormitories.” Fischl was reluctant to believe he had found the artwork of a family member, so he inquired more with the curator. His family discovered 30 pieces done by Fischerova, and he realized that the artist was in fact his cousin when he recognized a sketch of his grandparents’ living room. His family has since started Sonja’s Legacy Foundation to educate people about the Holocaust. He speaks in high schools and museums throughout New Jersey.

Fischl left Palestine because of violence and bombings and returned to Prague so he could try to finish high school there. After two months in Prague, Fischl left and went to Paris because of the Communist takeover in Czechoslovakia. Eventually came to the United States, where he received a bachelor’s degree from City College of New York and his doctorate from the University of Michigan. He has been teaching at Drexel since 1966.

Fischl recalled being one of two Jewish professors in the electrical engineering department, which used to be known as the Jewish department. He said, “I am amazed by how big Hillel is here [at Drexel]. It’s a totally different world.”

Fischl said he wants people who attended the event to understand that prejudice is horrible but indifference is worse.

“I think the worst part was the indifference. We were two families in this village of 15, and no one did a damn thing to help us. When we came back, we were accused of being collaborators. There were terrible things being done to us, and the others looked away and didn’t interfere,” Fischl said.

Fifth-year international area studies major Emily Jessup said, “I came out with a new perspective. When [Fischl] told us that he doesn’t have friends from high school or any reunions to go to, that really hit home. I realized what a ‘secure’ environment we all live in, and that’s sometimes taken for granted. I thought the discussion was really intense, but I enjoyed it. It makes me sad, but I think it’s important to learn about these things.”

Engineering professor Peter Herczfeld was originally scheduled to speak about growing up in Nazi-occupied Hungary but was unfortunately unable to attend the event due to illness.

Fischl’s story of Sonja’s legacy was scheduled to complement Yom HaShoah, Holocaust Remembrance Day, on April 7. Drexel Hillel also organized a memorial service and discussion with yarzheit candles to recognize the day.

More information on Sonja’s Legacy Foundation can be found at www.sonjaslegacy.com.