Few remember the year that Powelton Village was taken hostage. There is no blue marker, mural or memorial plaque on the southeast corner of 33rd and Pearl streets to commemorate the yearlong standoff with a cult-like group that ended with a Philadelphia police officer dead. Not even the house at 309 N. 33rd St, where the events centered, remains: only a blank brick wall and an Amazon locker occupy the corner today.

Many remember another date: May 13, 1985, when the Philadelphia Police Department dropped a two-pound bomb from a state police helicopter onto a block of West Philly rowhomes, killing 11 members of the radical black eco-liberation group known as MOVE – including five children – and forever branding Philadelphia as “the city that bombed itself.”

After firing thousands of rounds in a second, hours-long shootout with MOVE, which was holed up in a rowhome-turned-bunker, police allowed 61 homes on Osage Avenue to burn after the bombing. Two hundred and fifty people were rendered homeless in an attempt to flush out the inhabitants of one. The photos evoke the aftermath of the bombing campaigns of World War II: pick Dresden or Tokyo, 1945. When the siege ended, only two MOVE members out of the thirteen present had survived.

6221 Osage Avenue will forever be the site of the “MOVE house” because of May 13. But just steps from Drexel University’s campus, D.P. Dough or the Apple Pi Lambda house, at 309 N. 33rd Street, history took a turn that would lead to the 1985 MOVE bombing.

MOVE is not an acronym. It does not stand for anything. Instead, the name is a manifesto for a group that stood fervently by its causes. In 1972, MOVE founder Vincent Leaphart – a Korean War veteran sick of a world beset by racial and environmental injustice, police violence, industrialization and technology – took the name John Africa in honor of humanity’s birthplace. Functionally illiterate, he dictated a manifesto calling for liberation from those societal ills for all living things: black, white or other, both human and animal. As John Africa saw it, all living things were on the move, together.

In today’s alienated era, where open admiration for Ted Kaczynski’s neoluddism is becoming mainstream, back-to-nature living mixed with black nationalism seems quaint. But John Africa’s total rejection of government authority took on a deeper meaning in 1970s Philadelphia, an era embodied by police commissioner, then mayor, Frank L. Rizzo. Black Philadelphians were subjected to flagrant racism in housing, education and routine police violence. Under Rizzo, student protests for equal education were put down with force, a black-only curfew was enforced, Black Panthers were harassed and efforts to hire black police officers were quashed. In 1971, on the campaign trail, he told voters to “vote white.”

In this climate, MOVE found a receptive audience among young people seeking an alternative. Taking the surname Africa, they adopted John Africa’s tough guidelines on vegetarianism, rejecting technology, strict sobriety, exercise, communalism and respect for life – not to mention zealous public protesting. MOVE members brought bullhorns and disruptions to church services, environmental demonstrations and the Philadelphia Zoo: anything representative of the establishment. These highly performative protests brought the group media attention and new members, but drew Rizzo and the PPD’s ire; clashes with police became frequent and violent, and arrests incessant, but charges were rarely serious.

By 1974, the group had established a communal home at 309 N. 33rd Street in Powelton Village. Powelton was then an idyllic countercultural hub, home to other communes and predominantly white. Even there, MOVE proved a polarizing neighbor; while some residents, including Drexel students, embraced a live-and-let-live attitude, for others, MOVE’s practices of burying waste in the yard and then-novel composting were too odorous, and the vermin intolerable. Furthermore, the house was plagued by stray animals, neighbors saw the children unclothed, unschooled and malnourished, and some residents reported being harassed or attacked. City health inspectors were routinely turned away by the group.

On March 28, 1976, police were called to the MOVE house by a neighbor over a disturbance. When they arrived, a typical confrontation ensued, replete with billy club bludgeoning, arrests made and police eventually dispersing. But MOVE alleged that in the fray, the three-week-old Life Africa, an infant born in the house, had been killed.

Police dismissed the story. But, sworn to secrecy, Philadelphia Inquirer staff and city representatives, including Lucien and Jannie Blackwell, were invited to the MOVE home and shown a body. The Inquirer would report on the experience the following week, but the killing would never be legally substantiated. MOVE refused to recognize the courts’ authority, and so with no identity, no body, no autopsy and no testimony, there was no legal investigation. Current MOVE member Mike Africa, Jr. would suggest in 2020 that the baby had been born stillborn after the pregnant Rhonda Africa was beaten in the 1976 melee.

With the relationship between the police and MOVE rancorous, the group turned to blasting the neighborhood with loudspeakers, broadcasting its ideology at Pearl Street around the clock. By 1977, members of the group started facing more serious charges, and the group further militarized with guns, baseball bats and khaki uniforms. On May 20, they began broadcasting a list of grievances for police, who had begun round-the-clock surveillance, demanding the release of three members being held on felony charges of riot and terroristic threats.

Soon, rumors began swirling that Mayor Rizzo would order a raid on the property and remove the remaining members by force. An armed standoff between MOVE and police ensued.

“Brandishing shotguns, rifles, and machine guns, MOVE members made it clear last Friday that they were not to be forced out of their home located at 33rd and Pearl St. That same evening, nearly 200 Philadelphia policemen surrounded the building while neighborhood residents awaited the outcome of the armed confrontation,” Pat Graupp reported for The Triangle on May 27, 1977.

“Nearly a week later, police, headquartered in the National Guard Armory [now the Arlen Specter Squash Center], are still to be seen patrolling the northern part of campus… In a statement made on Wednesday, Mayor Frank L. Rizzo stated… ‘If there’s any shooting, they’ll start it and we’ll finish it.’

…The illegal weaponry displayed by MOVE is a cause of great concern for police, residents, and students alike. However, one member explained to me that MOVE is not out to harm anyone. They merely wanted to show the police what they were up against should they decide to enter the house. Subsequently, the police have kept their distance,” Graup wrote.

As the temperature climbed and the standoff dragged from days into weeks, the situation – implausibly – started to become routine for students. In a satirical graduation edition entitled The Quadrangle, published June 3, pseudonymous writer “Senor Itis” wisecracked,

“The recent attempt to evict the members of MOVE from their rat-infested headquarters… became successful after a two-week campaign by the Philadelphia police. Unfortunately, MOVE moved into the site of the new [Myers Hall], halting construction…

One intrepid Quadrangle reporter braved the flashy show of weaponry displayed by MOVE in order to ask them why they chose the uncompleted dorm as the site of their new headquarters. Their fearless leader replied, ‘Since we don’t believe in any establishment, this is the perfect location. It has no plumbing, no floors, no roof, and in many places, no walls. It is perfectly natural in its architecture, just what us back-to-nature movement people like to see…’”

By July, after eight weeks, the PPD sought court permission to barricade the property. Unable to make MOVE move, police wanted to starve them out. But, as always, the group doubled down and mugged for the cameras.

“Members of the revolutionary group MOVE stated that they will not be starved out of their residence if the federal court approves the blockade that a community group is seeking,” Neil Schmerling wrote for The Triangle, published July 15.

“Members of MOVE believe that they have been subject to excessive police harassment. Ishongo [Africa] stated that ‘the Philadelphia cops are the biggest gang in the city.’ He said that ‘Rizzo has had his foot in our ass ever since our existence and that if he knew of a way to get us out of here, he would,’” Schmerling relayed.

As the months dragged on, competing opinions ran in The Triangle.

“It’s disturbing to realize that the City of Brotherly Love is resorting to a tactic that seems almost medieval… At best, it can only worsen the already bad feelings between the group and the police; at worst, it could end in a real tragedy…. The Federal courts must decide whether the police have the right to blockade the house and deprive the residents of food. Hopefully, they will not allow this barbarous practice. Starvation… should not be used as a tool by the police,” Anita Brandolini, managing editor, wrote in the July 15, 1977 issue.

“Clearly, something must be done. MOVE cannot be allowed to continue terrorizing the community, nor can the law enforcement agencies ignore a direct threat to the safety of so many people. The proposed blockade would solve so many problems and minimize the danger to the surrounding community, the MOVE people themselves, and the police. It is a sane answer to an insane situation,” Denise Zaccanigno, production staff member, rebutted in the July 22 edition.

Meanwhile, police enlisted a series of negotiators, including civil rights activists Jesse Jackson, Andy Young and Philadelphian Walt Palmer, in hopes of getting through to MOVE.

As Palmer recounted to The Inquirer, those twelve months were arduous. Eventually, permission for the barricade was granted, and by March 1978, an area from 32nd to 34th Streets and Powelton Avenue to Baring Street was cordoned off with an eight-foot-high metal wall. With the barricade in place, Powelton residents required a police escort to move in and out of the zone.

In May, after 56 days in the barricade, and a year after the standoff began, Palmer managed to broker a multifaceted deal: the authorities could sweep the house for weapons and the three MOVE members held on felony charges would be released. Then, the remaining MOVE members would be voluntarily arrested and bailed out, one by one, and crucially, MOVE would leave Powelton Village by August 1, 1978.

But when August 1 rolled around, MOVE was still firmly entrenched. The police had been allowed to confiscate multiple inoperable guns, and had released the three jailed members, but the remaining members had not turned themselves in. MOVE had reneged on its deal.

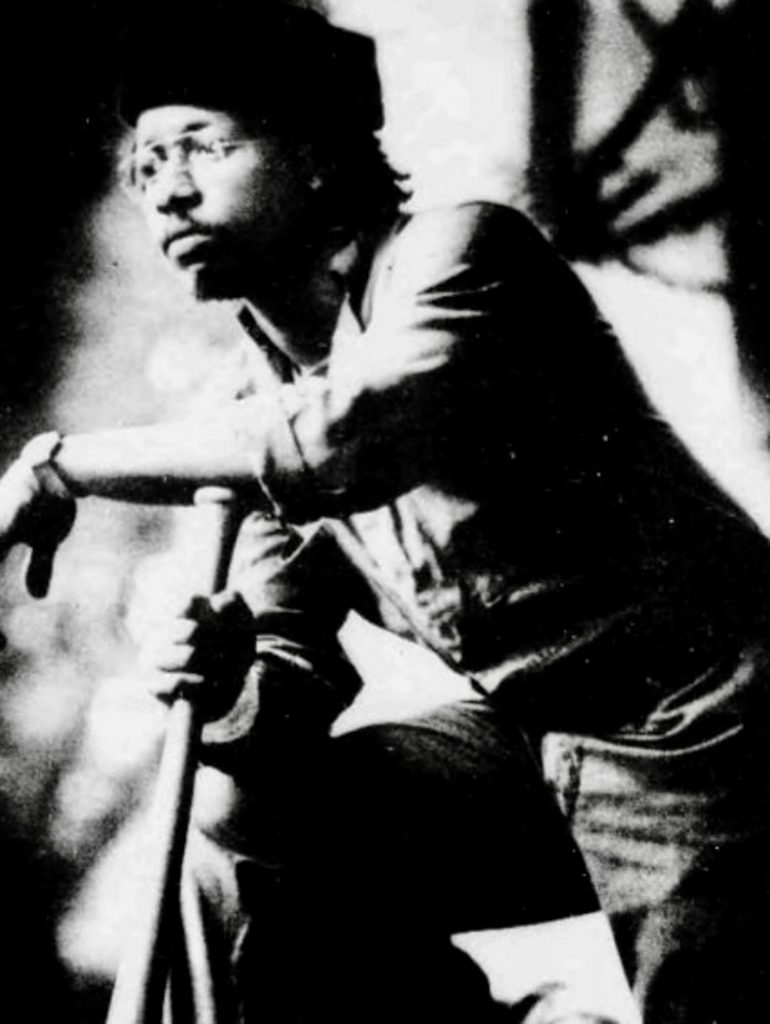

A photo run in The Triangle on Aug. 4 showed three revolutionaries perched on a fence along 33rd Street and the small crowd that persisted around them. After sticking it to the establishment, MOVE could triumphantly bask in the spotlight.

City officials were furious. Then-District Attorney Ed Rendell indignantly emphasized that an agreement had been signed and that the releases had been conditional, but he had little recourse besides issuing warrants for the remaining members’ arrests. More importantly, Mayor Rizzo had been humiliated.

So on Tuesday, August 8, tired of the games, Rizzo and police commissioner Joseph O’Neill made their move.

Police officers began arriving en masse by 4:30 A.M., per The Inquirer. They were armed with tear gas, high-caliber rifles, flak jackets and machine guns. Soon, demolition equipment appeared, and MOVE members retreated to the basement of the twin house.

At 6:09 a.m., police ordered the revolutionaries to surrender and come out. To no avail, they began to demolish the group’s improvised barricades, and soon heavy machinery was knocking through the boarded-up windows and walls of the house.

The fire department was instructed to set up hoses to begin flooding the basement. Eventually, police officers entered the house and began searching. Negotiator Walt Palmer entered with them and made direct overtures to the group to surrender. Still, no MOVE members emerged from the basement.

Soon after Palmer, frustrated, returned to the street, at 8:14 a.m., the first shot was fired.

Interviewed in 2025, he told The Inquirer that it came from the police line behind him. On Aug. 9, The New York Times printed, “Reporters across the street insisted that shots were fired from a sniper in a second‐story window in a neighboring house, but police discounted the story, though nearby houses were searched.” Though known to have had snipers trained on the house, police commissioner O’Neill would claim MOVE had initiated with four shots.

What followed was a minute-long firefight. By the time it ended, 52-year-old Officer James Ramp had been shot on Pearl Street. He would die of his injuries. Fifteen other police officers and firefighters were injured in the chaos.

Police, rallying, bombarded the house with tear gas, and 250,000 gallons of water were pumped into the basement. MOVE members finally began emerging: 12 adults and 11 children. The last to emerge was Delbert Africa, a spokesperson for the group, with his hands up. He was apprehended by two officers and savagely beaten in the front yard. The beating was captured on video and broadcast nationwide.

The house would be demolished by noon, despite being a critical piece of evidence, leaving a barren lot at 309 N. 33rd Street.

Nine MOVE adults were quickly charged with third-degree murder for the killing of Officer Ramp. The trial of the “MOVE Nine” was the longest and costliest criminal trial in Pennsylvania history, frequently derailed by the members’ protests. The defendants demanded to forgo a jury trial, attempted to be tried jointly, refused to consult with their lawyers, and, having attacked court staff, were eventually barred from appearing in the courtroom as a group.

All nine were convicted by the judge and sentenced to 30 to 100 years in state prison.

Three police officers would be charged in the assault of Delbert Africa. All three were acquitted.

“Delbert Africa wasn’t a man, he was a savage,” police commissioner O’Neill would later testify at the officers’ trial.

John Africa, who had been living in upstate New York, would relocate with the remaining MOVE members to Osage Avenue near Cobbs Creek Park by 1981. They would soon begin broadcasting their manifesto to the neighborhood by loudspeaker.

The vacant lot on N. 33rd Street would sit vacant for over a decade, until 1989, when it was purchased and redeveloped into three duplexes marketed toward students. The Amazon Hub locker was installed around 2020. Intentionally or otherwise, no trace remains of MOVE’s chapter in Powelton Village history.