A recent study in the Journal of Traumatic Stress, authored by Drexel assistant professor Jonathan Purtle, concludes that the majority of the legislation addressing post-traumatic stress disorder focuses on veterans, neglecting civilians with the disorder.

PTSD is commonly viewed as a “wound of war.” In fact, more than 90 percent of federal legislation that explicitly addresses PTSD mentions it in reference to military personnel. Similarly, more than 90 percent of these bills sought to address PTSD developed due to combat.

“There is a ton of research on PTSD in civilians,” Purtle explained, who is an assistant professor at the Drexel University School of Public Health. However, this research has not translated into widespread action. This inaction is due to several factors. First, the public lacks knowledge about the disorder’s prominence among civilians. Almost eight percent of civilians are reported to suffer from PTSD. However, police officers, physicians, emergency department personnel and nurses do not screen victims or suggest that they get screened. According to Purtle, society has systems to respond physically and legally to traumatic events and crimes via hospitals and arrests, so the key is to educate those already in the system. People such as teachers and police officers could give the victims the basics of PTSD, let victims know that their symptoms are normal and provide a link to further information.

Another factor limiting treatment for civilians is that there are not enough providers of said treatment. Even when treatment is available, those with the disorder may be uninsured or underinsured. Purtle noted that the Philadelphia Department of Behavioral Health has been doing a great job at helping the uninsured, however. “This is where public policy comes in,” he said.

According to Purtle, the criteria for diagnosis changes with each edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. According to the current edition, it must be a “unique” event. “[The] event is perceived as a threat to life …” he explained.

Civilians develop PTSD due to various traumas, which include violent injuries, car accidents, sexual assault, natural disasters, physical assaults and abuse, or surviving a life-threatening illness. Witnesses to traumatic events develop PTSD, as well. For example, 11 percent of the children who stood by the finish line at the Boston Marathon bombing . Women are more likely than men to develop PTSD, at a rate of 10 percent compared to 5 percent.

A considerable amount of the research on civilian PTSD concerns survivors of traumatic injuries. Survivors with PTSD were less likely to have returned to work a year after they were injured compared to survivors without PTSD. A program based in Philadelphia, Healing Hurt People, focuses on this population. The program is affiliated with the Drexel Center for Nonviolence and Social Justice, and it was founded by Theodore Corbin, an assistant professor in the Department of Emergency Medicine at the Drexel University College of Medicine. Corbin was an emergency physician at Jefferson University Hospital, Purtle explained, who worked as Research Director for the Center for Nonviolence and Social Justice and therefore was involved with the program. Purtle said that Corbin treated his patients’ physical injuries, but then had to send them on their way. He realized that there was no prevention of retaliation violence or recurring victimization.

A division of Healing Hurt People began at Hahnemann University Hospital, which is affiliated with Drexel, in 2008, and another began at St. Christopher’s Hospital for Children in 2009. There are two social workers from the program at each hospital, who talk with the patients and follow up by phone with those discharged.

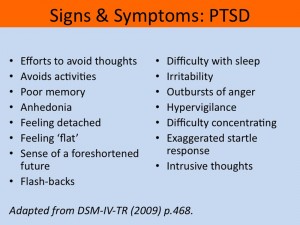

People react to PTSD differently and the symptoms vary. They may suffer from panic attacks, recurring nightmares, or flashbacks. Some withdraw emotionally, while others try to avoid situations that trigger memories of their trauma. Still others experience hyperarousal and startle easily. Such symptoms may take months to appear, but early evaluations can help determine if someone is at risk for developing PTSD. Usually, the disorder cannot be diagnosed until a month after the trauma. Until that point, PTSD is hard to differentiate from acute stress disorder.

Treatments for PTSD include cognitive processing therapy, prolonged exposure and eye movement desensitization and reprocessing. CPT involves changing the way patients thinks about their trauma. Prolonged exposture therapy’s goal is to minimize the patient’s fear from trauma. The treatment usually begins by tackling the less traumatic memories first. In eye movement desensitization and reprocessing, patients think about their traumatic memories and follow the movement of their therapist using only their eyes. For example, the therapist could finger-tap on a desk. There are also medications available for those with the disorder, such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors.

Scientists do not currently know the exact cause of PTSD, but one prominent suggestion involves how the brain stores memory. “[The theory] is about how [the memory] was encoded in the brain,” Purtle explained. When an individual experiences an overwhelming human experience, it is not encoded into language, which would occur with a normal event.

“There’s more and more interest in biological theories … and genetic research,” Purtle said. “It’s probably a little bit of everything.” The language system essentially shuts down. Because the memory is not encoded normally, it becomes “stuck” in the brain.