As an institution within a major metropolitan area, Drexel University has lived through times of great divide within society; since its inception in 1891, both the university and its students (though sometimes, not at the same time) fought inequality and segregation in key historical turning points, such as the Civil Rights movement and other protests that took root in Philadelphia.

In 1967, the university planned to build its first dormitory to accommodate some students who wanted to stay close to the school instead of commuting and follow the West Philadelphia Corporation — created by Drexel and the University of Pennsylvania — goal to redevelop West Philadelphia and accomplish the higher goal of molding Philadelphia into an economic and industrial engine like it once was. This first building was set to be constructed on 33rd and Arch St., where there was a majority Black population that would have been displaced; specifically, 574 families would have been displaced, of whom 90 percent were minorities, according to James Wolfinger who wrote a chapter about race and Civil Rights in a book co-edited by Richardson Dilworth and Scott Knowles called “Building Drexel: The University and Its City.”

Students at the time realized the importance of community outreach and wellbeing, and decided to voice their concerns by forming a coalition named “East Powelton Concerned Residents.” This group of students and community residents protested to call for the university to see West Philadelphians as equals and not force them to leavee where they have lived their entire plans for University construction plans, The Triangle reported in 1967.

Penn and Temple students joined the protests that gained attention through revolutionary newspapers and by illegally occupying Drexel buildings. The East Powelton Concerned Residents organization was able to eventually get a meeting with Drexel University’s soon-to-be president William Haggerty. However, expansion continued.

These were not the only social issues Drexel faced at that time, and this movement of “liberation” found a cause tied to the West Philadelphia community to fight for Black rights and Black identity on campus. However, there was a concern regarding the lack of Black students within the student population.

In 1967, there were only 36 Black students attending the University, representing a mere 0.7 percent of the student population. But in 1970, that number grew to 302, representing 3.4 percent of the student body. Although some reports say that this jump was because the school began to report its evening classes enrollments in 1969, the climate became more hostile since this increase.

Students were beginning to complain about their peers performing in blackface for talent shows according to articles published by The Triangle in the late 1940s and 1950s. Many students were writing that the school made them feel “invisible.” That to fit in they felt pressured into “dressing white middle-class, acting, and even talking white middle class.” By “the second year at Drexel,” wrote Regina Arnold in The Triangle, “you become bitter about the whole scene.” Black students received 16 hours a week of airtime on the school’s radio station for “The Black Experience in Music,” and the glee club had significant African-American representation. But overall, “No student organization makes any attempt to enfranchise the members of the Black student population,” wrote one reporter.

Even in 1968, wrote another reporter, Drexel had only a few black employees, and almost all worked in “menial jobs.” There was no African-American history class, no Black faculty members, no authors of color on campus. For many Black students whose “experience has been sheltered, meaning you’ve dealt almost exclusively with Blacks,” wrote one woman, “the transition that is made in coming to a place like Drexel University can be a living hell.”

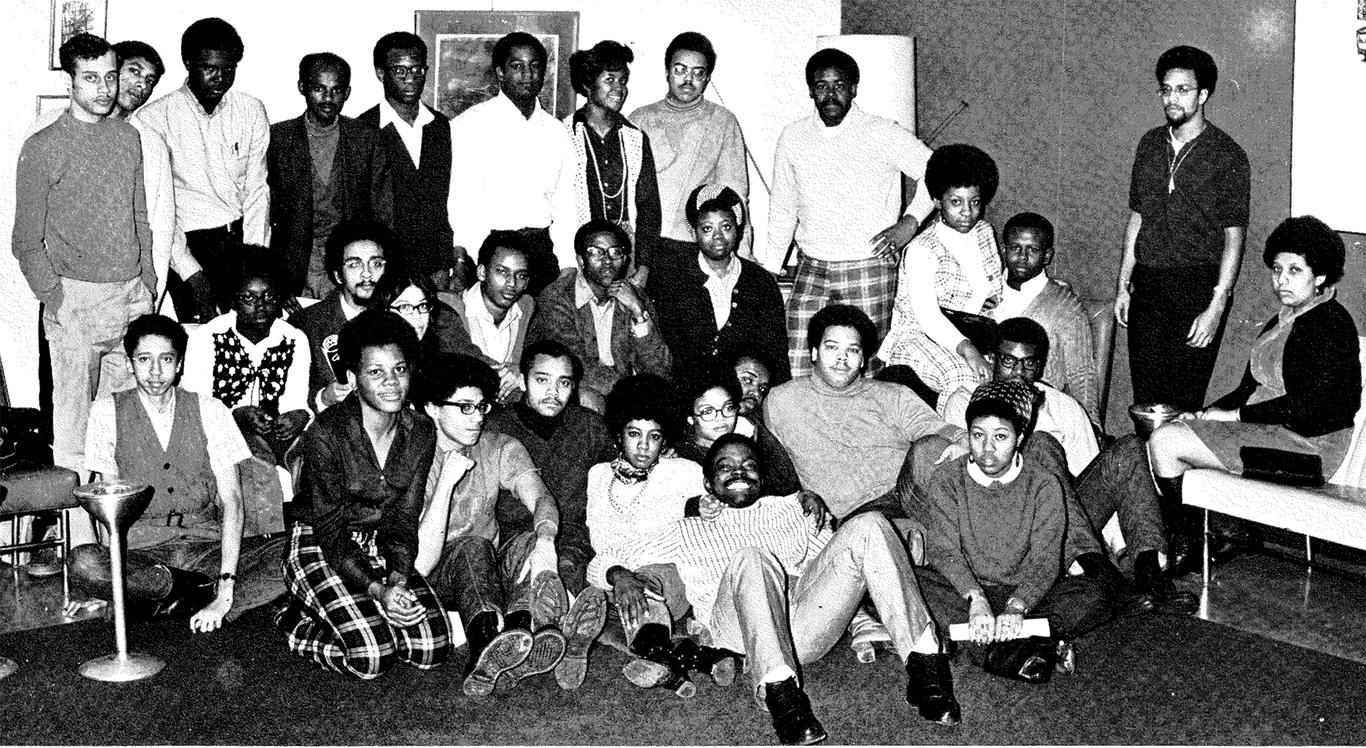

One of the first actions taken to combat the small Black population at Drexel was the formation of the Afro-American Society. This organization was tasked with holding informational seminars for African Americans to push them to attend Drexel, in addition to holding lectures that educated participants on Black culture and power, as The Triangle reported in 1968 and 1969. The Afro-American Society was also used as a platform to voice the concerns of the small, but powerful Black population; they ultimately pushed Drexel executives and administration to hire more Black professors, add more African American history classes to its curriculum, and admit enough Black students to substantiate a 10 percent Black student population.

Despite the robust attempts to change Drexel’s stance on inclusion, little was done to appease the Black students at the time. The growing tension between white and Black students ceased the administration’s initiatives to appeal to the Black student population’s concerns. According to Wolfinger, Dilworth and Knowles: “critiques of the school angered some white students and pushed the administration in halting ways to be more attentive to black needs.”

We are now in 2021, living during historic times. Over the summer of 2020, during the Black Lives Matter protests, Drexel had numerous statements and incidents regarding the situation and there were many controversies about the university’s involvement in the civil unrest that took place multiple times in Philadelphia.

As protests against racial injustice were ongoing, Drexel’s Police Department was involved in a big incident on 52nd Street. People started marching from 33rd & Market St, Mario’s location, towards the University of Pennsylvania’s police building. Students, alumni and faculty, along with members of multiple organizations were protesting on May 31, 2020, when DUPD was seen committing acts of police brutality on 52nd street in a predominantly Black neighborhood, The Philadelphia Inquirer wrote.

“One officer was photographed holding the arm of an individual. According to an investigation into that incident, the officer was assisting the individual, who was in need of medical attention,” according to a statement posted by Drexel University on July 28, 2020. Two days later, on July 30, 2020, Drexel posted another statement, “Correction and Apology: Drexel Police Activity on May 31,” saying that “the Drexel officer was attending to the individual after he had been handcuffed by Philadelphia Police.” Penn and Drexel’s students and officers on the universities’ campuses called for defunding the colleges’ police departments, The Inquirer reported.

Drexel was part of another controversy regarding the presence of the National Guard on campus. This situation created unrest among Drexel students amid the protests against racial injustice and police brutality, according to a Triangle article written by Jason Sobieski.

The majority of Drexel students were not pleased with the situation and immediately contacted the administration. President Fry disclosed that The Armory is the property of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania making Drexel unable to refuse Mayor Kenny’s request.

“I acknowledge the anger, frustration, pain and, frankly, fear that was caused by seeing National Guard vehicles on or close to our campus,” Fry said in an email statement sent on the following days. “Drexel is not condoning violence against peaceful protestors.”

During a period of civil unrest for the United States and the rest of the world, Drexel students got involved in multiple anti-racist actions.

Student Tianna Williams is the only undergraduate student co-chair that is part of the Anti-Racism Task Force created at Drexel University, a DrexelNow article wrote. She is the president of the Drexel Black Action Committee (DBAC), a member of the National Society of Black Engineers as well as a student ambassador for the Student Center for Diversity and Inclusion. The student was named the Face of Change at Drexel University due to her constant hard work and effort put into multiple organizations that fight for social justice.

“I think it gave us and other Black students, Black faculty and staff, [the ability] to really turn the eyes on the University and be like, ‘You know, this is just part of a larger issue of systemic racism,’” she said. The student is hopeful and fighting to introduce multiple anti-racist changes among the university’s policies.

The Black Lives Matter movement also made the University create the Anti-Racism Task Force and the Center for Black Culture. The university promises multiple greater anti-racism efforts and to become better partners and stronger advocates on anti-racism. “Sharde [Johnson] will lead a steering committee to develop the Center’s mission and ensure that it serves as a home to all Drexel students, faculty and professional staff, while increasing knowledge of the people, histories and culture of the African diaspora and its many contributions to the world,” Fry said in a statement announcing the creation of CBC. People interested in The Center for Black Culture should contact [email protected].

To not let the movement die and keep engaged in these social causes, there has been a lot of advocacy for social change among Drexel students through social media.

The Instagram account @blackatdrexel is a space for students of color to make anonymous confessions of instances where they were victims of racist aggressions or microaggressions on campus. This account was created on July 1st by a student who saw similar accounts created on Penn and Temple’s campuses. Another account that gained a lot of traction on Instagram is @drexelforjustice. The creators of the account frequently post about Drexel’s effect on West Philadelphia due to gentrification, defunding Drexel University Police Department and multiple other social justice causes. They organized multiple online and physical events over the summer to express their advocacy goals.

Additionally, the DBAC as well as Drexel Black Student Association organized multiple events over the summer in an effort to inform and educate people about racial injustice and police brutality against the Black community.