I watched Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood as a child, and like most ’90s kids, I have some sort of fond nostalgia for the PBS show: the sweaters, the sneakers and the soft-spoken puppetry.

I also remember finding out that Sesame Street has been running since 1969. Since I was an only child who never had to share the TV, I had taken Elmo and Big Bird as my show, though their likeness seemed to fill every preschool wall and toy box I’d ever encountered.

But even members of Generation X, the oldest of which are now 48 years old, had been raised with the old Cookie Monster, who seems to be the same even when he’s covering Carly Rae Jepsen’s “Call Me Maybe” with the Sesame Street staff in their cubicles. If Cookie Monster was born in ’69, then he would be one of the first members of Generation X too.

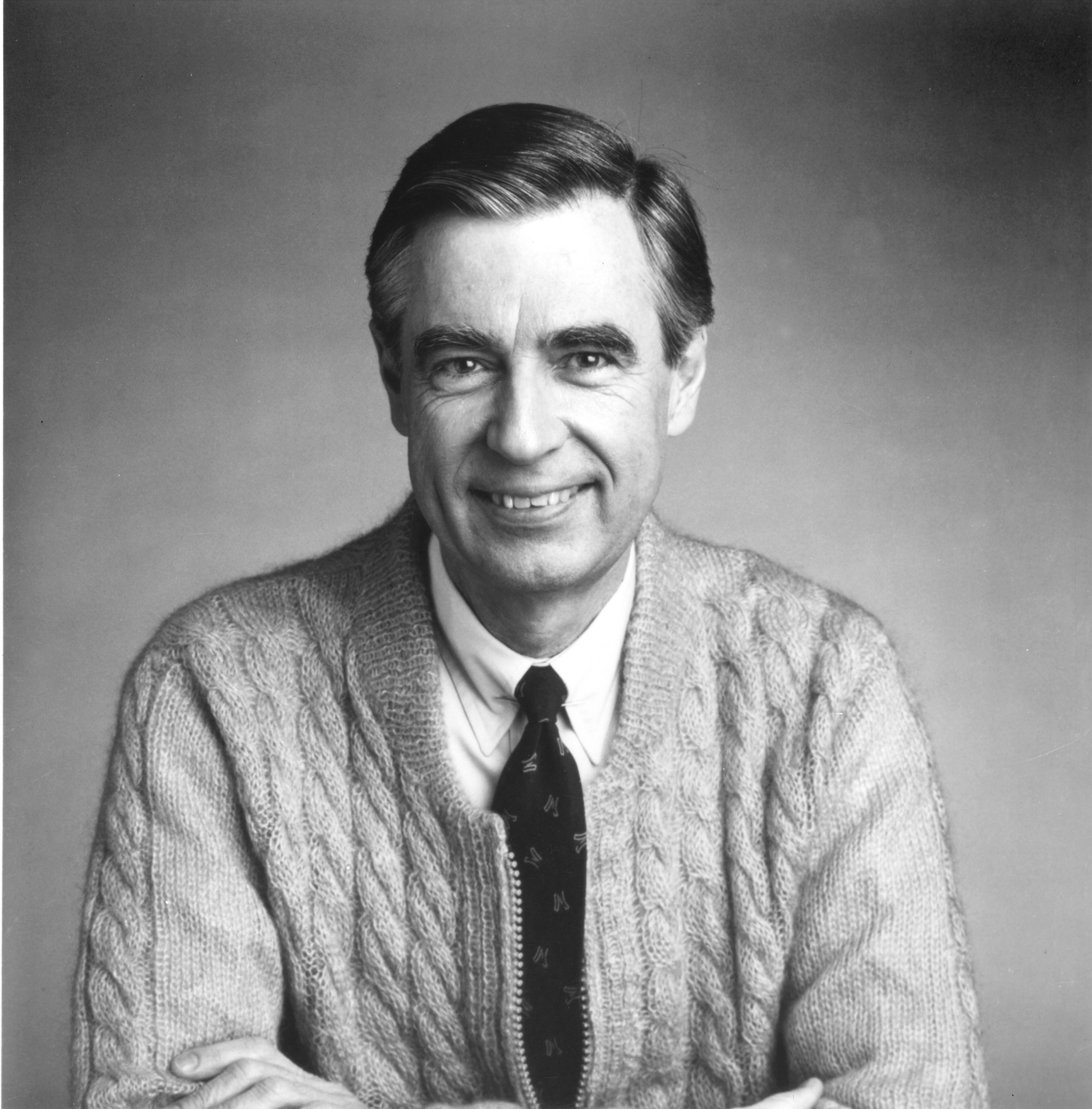

Fred Rogers, on the other hand, was both a character and a maker, a human being that maintained the same heartwarming consistency during the show’s run from 1965 to 2001. When he passed away in 2003, I was six years old, but I’d never processed it fully because I would still be awake to sing “It’s a Beautiful Day in the Neighborhood” with him each morning. If only I were as unapologetically consistent with my mornings now as I was then.

Rogers was a Pennsylvanian, born in 1928 Latrobe, a town 40 miles east of Pittsburgh. It is little known that Rogers was overweight as a child and frequently bullied by other children in the neighborhood. This same boy would grow up to devote his life to children’s ministry through the television — the very thing that threatened childhood as Americans recognized it. Rogers even testified in its defense before Congress in 1969, four years after the show’s first broadcast on PBS.

He referred to television as “our form of communication,” a medium that was able to reach kids individually to affirm their worth. Indeed, Rogers was a man of counterculture, using this medium to subtly protest the major world wars of the late 20th century by assuring viewers that the children of the neighborhood would be protected and cared for by the adults and called upon parents to do the same. What was it that made this children’s show so radical in the era of Vietnam, the Gulf War and space shuttles? He communicated to children that he liked them just the way they are.

Such ideas of children being ‘special’ tend to appear idealistic, but Rogers toiled long to bring his message to American children, operating on a budget of $6,000 when such money would have paid for “less than two minutes of cartoons.” He composed all of the songs, wrote all of the scripts and played almost all of the puppets, deliberately maintaining a steady and attentive pace to stand in solidarity with children, the most vulnerable members of every population around the world.

It was Rogers’ convictions that show him to be a radical, indeed; this grandfatherly figure, of the same spirit from his first and last appearances on American television, was truly a man of conviction, maintaining his dedicated efforts to peacemaking and encouraging a strong sense of self in children.

How do you remember Rogers, whether you had missed the opportunity to watch Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood as a child or grew up putting on your sneakers with him every morning? Even when Mr. Rogers went to Washington in 1969, Senator Pastore — the first Italian-American to serve as a senator or governor — told Rogers during the six-minute testimony that he’s “supposed to be a pretty tough guy” but that he had “goose bumps” after hearing Rogers telling children via television that their feelings are okay is “more dramatic than showing something of gunfire.”

Rogers received very few criticisms during his long career, but one claim brought against him was that he affirmed children excessively, which created a culture of narcissism. Such worries are indeed valid within the context of modern American parenting, but Rogers held a firm belief that children are already subjected to many negative forces and often learn from adults to hide away their emotions or ignore them entirely. When children learn to recognize and affirm their emotions, they are better equipped to reconcile them to their reality, no matter how devastating it may be.

Most importantly, Rogers loved unconditionally. A Presbyterian minister since 1965, his relentless commitment to love others as they were rather than what the world expected them to be transformed our perception of mass media. His soft spokenness and righteous anger managed to shake the world of television consistently simply because he held children and adults alike to the standard of being themselves.

What about you? Are you holding yourself to the same standards of loving others and humbly affirming your very real, very present troubles? Let us hold fast to Rogers’ theology as we go about the everyday, even when we see others who do not do the same. It is okay to be vulnerable, and it is okay to be relentless. We are liked and loved just the way we are, so long as we are willing to be ourselves.